Step beyond the majestic yellow facade and discover the real soul of the Habsburg dynasty inside Schönbrunn Palace.

Support when you need it

Customer service to help you with all your needs from 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.

Fast and online booking

Choose the best option for your needs and preferences and avoid the lines.

Top attraction in Vienna

Discover Vienna’s most famous palace and step into centuries of imperial history.

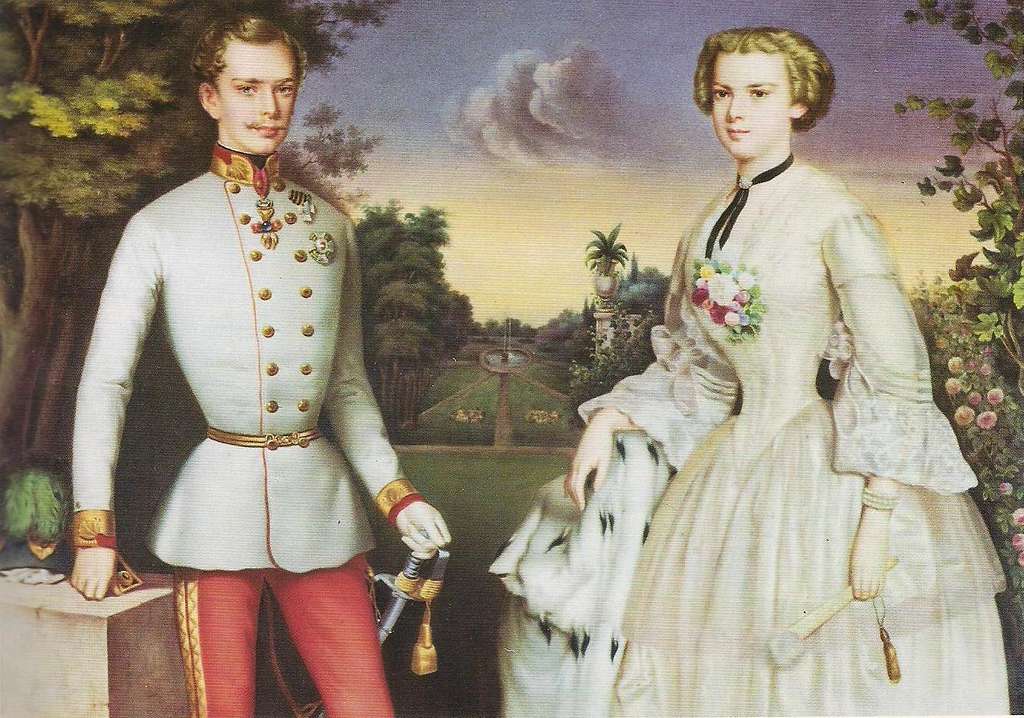

With your Schönbrunn admission ticket, you can’t see all 1,441 rooms, and honestly, you wouldn’t want to either. The palace opens around 40 to 45 carefully selected chambers to the public, and among these, five rooms stand out as absolute showstoppers. These aren’t just pretty spaces with fancy furniture. Each one tells a specific chapter of European history, from the artistic revolution of the 18th century to the tense moments of the Cold War.

What makes these five rooms essential? They represent the pinnacle of Rococo art, they witnessed world-changing events, and they reveal the intimate lives of the people who shaped an empire.

Picture a ballroom stretching over 43 meters long and nearly 10 meters wide. This is where the Habsburg court showed the world what power looked like. The Great Gallery was designed as the ultimate stage for imperial theater, hosting state banquets, diplomatic receptions, and those legendary Viennese balls that defined an era.

But what really captures your attention are the frescoes by Italian artist Gregorio Guglielmi. These aren’t just decorative paintings. They’re sophisticated propaganda, glorifying Empress Maria Theresa’s reign and reinforcing her legitimacy as ruler.

The room didn’t retire after the monarchy fell. During the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, European powers gathered here to redraw the continent’s borders after Napoleon’s defeat. And in one of history’s more surreal moments, this opulent Rococo masterpiece became the backdrop for a Cold War summit between JFK and Khrushchev in 1961.

This room earned its place in history because of 45 minutes in 1762. That’s when a six-year-old child prodigy named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart gave his first concert before Empress Maria Theresa and her court.

After finishing his performance, little “Wolferl” didn’t bow politely and back away as protocol demanded. Instead, he jumped into the Empress’s lap, threw his arms around her, and kissed her enthusiastically. Maria Theresa, who ruled one of Europe’s most powerful empires, apparently found this delightful rather than scandalous.

Beyond this iconic moment, the Hall of Mirrors served as an audience chamber for special occasions.

If you only have time to fully appreciate one room in Schönbrunn, make it this one. The Million Room is universally considered one of the most beautiful and extravagant Rococo rooms in the world, and its name tells you everything. The cost was so astronomical in the 18th century that it was simply called “the million,” as in, incalculable.

The walls are paneled with an extremely rare tropical wood called rosewood or “Feketin.” But the real magic happens within 60 gilded rocaille cartouches embedded in these panels. Inside each frame, you’ll find something unexpected: collages made from Indo-Persian miniatures depicting scenes from the Mughal Empire in India.

They were valuable miniatures that members of the imperial family personally cut up and reassembled into new compositions, like aristocratic scrapbooking. What seems like artistic vandalism today was considered refined appreciation in the 18th century.

Few spaces in Europe concentrate as much personal and political history into one chamber. Originally the study of Emperor Francis Stephen, this room became something entirely different after his sudden death. Empress Maria Theresa transformed it into a private memorial sanctuary for her beloved husband, installing precious black Chinese lacquer panels and surrounding herself with family portraits she personally commissioned.

If the Great Gallery represents the height of Habsburg power, this room represents its final chapter. The Blue Chinese Salon, decorated with Chinese wallpapers and chinoiserie elements, might be the most historically significant space in the entire palace for modern Austria.

On November 11, 1918, the last Emperor of Austria-Hungary, Charles I, sat in this room and signed his renunciation of participation in state affairs. That single act dissolved the monarchy and ended more than 600 years of uninterrupted Habsburg rule. The dynasty that had shaped European history for centuries ended not on a battlefield but in a blue-decorated salon.

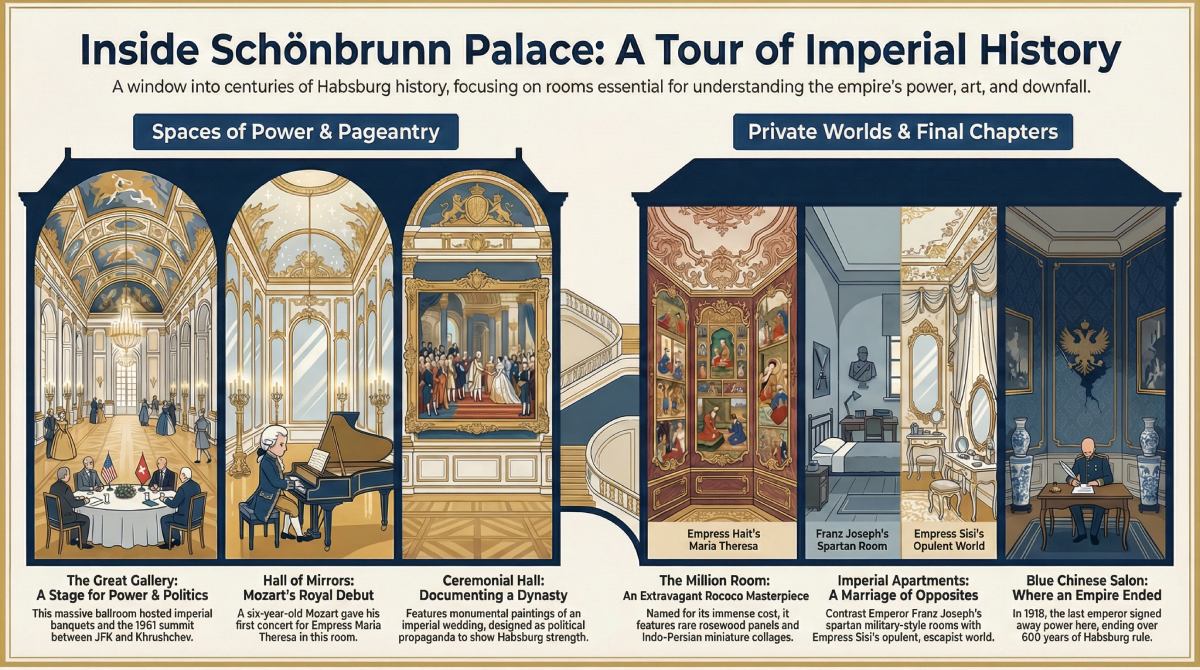

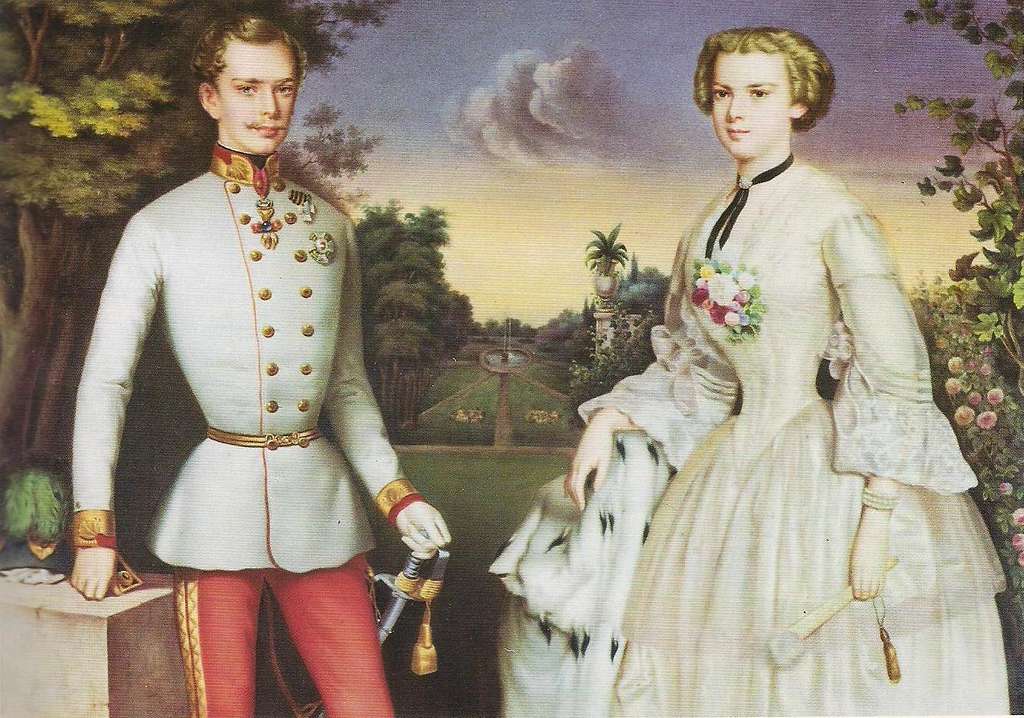

This wing tells the story of Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth (Sisi), the couple who presided over the empire during both its zenith and its eventual decline. What strikes you immediately is how these apartments reveal two completely different personalities, two opposing worldviews, and ultimately, a marriage that existed more on paper than in practice.

You might expect an emperor’s private quarters to drip with gold and luxury. Franz Joseph’s rooms tell a different story entirely. His study and bedroom are remarkably austere, almost spartan in their simplicity. They reflect the famous military discipline and relentless work ethic of the “emperor-bureaucrat” who governed the empire for 68 years.

The most striking element? The simple iron campaign bed where he slept most of his life and where he died in 1916. Franz Joseph genuinely lived like a military officer, rising at dawn, working through mountains of paperwork, and maintaining the kind of rigid routine that would break most people.

Cross from Franz Joseph’s quarters into Sisi’s apartments, and you enter another world entirely. The contrast couldn’t be more dramatic. Where his rooms speak of duty and denial, hers overflow with luxury, personal expression, and a desperate need for freedom.

But these rooms tell a more complex story than simple luxury. Sisi was arguably the most famous woman of her era, a 19th-century celebrity whose beauty was legendary and whose rejection of royal duties scandalized Vienna.

She traveled constantly, sometimes for months, escaping to Hungary, Greece, or wherever she could find distance from her mother-in-law and the suffocating protocols of the Habsburg court.

Now we shift centuries and sensibilities. The East Wing transports you back to the 18th century and the reign of Empress Maria Theresa, the formidable matriarch who transformed Schönbrunn into the artistic marvel it became.

This small cabinet served as Maria Theresa’s private writing and work room, and it’s an absolute artistic fantasy. The walls aren’t actually covered in porcelain at all, they’re wooden panels meticulously hand-painted to imitate porcelain, creating a complete chinoiserie illusion.

Two rooms, the Oval Cabinet and the Round Cabinet, flank the Small Gallery and tell a more secretive story. Maria Theresa used these chambers for confidential conferences with her state chancellor, discussing matters too sensitive for public halls or even private apartments where servants might overhear.

Unlike the Porcelain Room’s clever imitation, these cabinets are decorated with authentic Asian lacquer, imported silks, and genuine porcelain from China and Japan. The materials alone represented enormous wealth, but their purpose went deeper than showing off. These rooms created an atmosphere of otherness, a space psychologically separated from the everyday operations of the palace.

This grand antechamber served as a waiting and reception area, but its real significance lies in the monumental paintings depicting the wedding of Maria Theresa’s son, Joseph II. These weren’t intimate family portraits. They were large-scale propaganda pieces, documenting one of the most important dynastic marriages of the century.

The paintings capture the full pageantry and political significance of imperial weddings, those carefully orchestrated unions that maintained alliances, secured borders, and perpetuated dynasties. Looking at them now, you’re seeing how the Habsburgs wanted their own history remembered: magnificent, ordained, inevitable.

Schönbrunn Palace is usually open daily from morning until late afternoon. Opening hours may vary slightly depending on the season, so it’s best to check in advance. Gardens and certain attractions within the complex may have separate schedules.

The palace is easily accessible from central Vienna:

Metro: Line U4, stop “Schönbrunn” or “Hietzing”

Tram: Lines 10 and 60, stop “Schloss Schönbrunn”

Bus: Lines 10A and 63A

By car: Paid parking available near the main entrance

Other things to do in Vienna

Vienna State Opera tickets >

St Stephen’s Cathedral tickets >